This story appears in the 2014 Special Edition of Rural Voices Forgotten or hidden from mainstream America, several rural areas and populations are isolated geographically, lack resources and economic opportunities, and have suffered through decades of disinvestment and double-digit poverty rates. Persistent poverty is most evident within several rural regions and populations, including the Lower Mississippi Delta, the rural Southeast, Central Appalachia, Native American lands, the colonias along the U.S. Mexico border, and migrant and seasonal farmworkers.

This story appears in the 2014 Special Edition of Rural Voices Forgotten or hidden from mainstream America, several rural areas and populations are isolated geographically, lack resources and economic opportunities, and have suffered through decades of disinvestment and double-digit poverty rates. Persistent poverty is most evident within several rural regions and populations, including the Lower Mississippi Delta, the rural Southeast, Central Appalachia, Native American lands, the colonias along the U.S. Mexico border, and migrant and seasonal farmworkers.

Among the most economically depressed areas in the country, addressing social, economic, and housing problems has proved challenging. To help better understand this issue, Rural Voices spoke with five housing experts, each with decades of experience providing housing and working with low-income families in persistent poverty areas. Their firsthand knowledge presents an unparalleled view into the harsh reality of families and communities grappling with long-term poverty. These experts offer their insights, passion, and commitment to help solve what is often considered an intractable problem.

What does poverty look like in your community or region?

Ann Cass: In Hidalgo County, Texas, one out of every three people in our community is poor. One out of every two children is poor. This poverty is lived out in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas, a region that has no viable public housing program. This means that, typically—usually—a child will be living in a neighborhood or colonia that looks like a shanty town in a third world country.

The families live in mobile homes with busted walls and ceilings, in shacks made of grocery store pallets or in sheds made out of old political campaign billboards. If you visit such a home, you will find two or even three families living in the same home.

Selvin MaGahee: I’m located in rural central Florida, and I work in rural communities throughout the Southeastern United States and Puerto Rico. There are many places in these areas that define persistent poverty. It looks like remnants of the economic and educational inequalities that have persisted since the post slavery/Jim Crow era throughout much of the rural south. There are still many racially segregated neighborhoods that contain a disproportionate share of substandard housing and other examples of economic hardship.

Half the students who begin kindergarten will not graduate from high school. In the midst of their long suffering I see resilience, persistence, creativity, and strength. I see a people who need hope.

-Ann Cass

Bill Bynum: Nationwide, one out of four persistently poor counties and parishes are located within the Mid South states. In Louisiana and Mississippi, over half of the states’ counties and parishes are classified as persistently poor. Within these counties and parishes, poverty and race are inextricably connected. Thirty-five of the region’s thirty-nine counties and parishes in which the African American population exceeds 50 percent have had poverty rates in excess of 20 percent consistently for the last three decades.

Tom Carew: One thing you can surely say about poverty in Central Appalachia: it is persistent. Since the War on Poverty began in the 1960s, Central Appalachia has remained at the bottom. That is not to say there has been no progress over the past 50 years. There is much to celebrate: safe drinking water, sanitary sewers, four lane highways, hospitals, good schools, the incidence of homes without full plumbing, a prime indicator of substandard housing, are at historically low levels.

Unfortunately even with all the improvements the region remains at the bottom compared to the rest of the country. In Central Appalachia, especially the coal fields, unemployment has increased as the demand for coal has decreased primarily due to the price of Natural Gas and Environmental concerns. It is very difficult to find replacement employers who can pay annual salaries of $60,000.

Ann Cass: If I were to sit at a table and visit with the head of the household in the colonias in Hidalgo County, the conversation would be terse, for these are people who work long hours for little pay and less relief, and many hold down two or three jobs at minimum wage. The conversation may well be guarded, for many of these families are of mixed-immigration status, and there is no telling when a beloved uncle or cousin will be picked up and “disappeared”—deported back to Mexico.

The children are children, and play and laugh and are affectionate. Yet, the educational system fails so many. Half the students who begin kindergarten will not graduate from high school. In the midst of their long suffering I see resilience, persistence, creativity, and strength. I see a people who need hope. As we attempt to offer them that hope, somehow we are gifted with hope by them.

Pinky Clifford: Here, on the Pine Ridge Reservation, poverty looks like the word “without.” The vastness of our area captivates visitors but it doesn’t take long for them to experience just how large it is out here. My thirty-five mile commute to work (one way) consists of two stop signs and two traffic lights (my driveway doesn’t count). When I say that poverty looks like the word “without” it means we do without adequate housing, jobs, health care, economic development, and improved road systems. In our area poverty looks like older trailers and manufactured homes in desperate need of repair or replacement. Poverty looks like the many roofs, windows, and doors that need replacement and severely overcrowded homes. Poverty makes us look like we don’t want to work or do anything for ourselves, and at the same time, poverty masks the positive in the community.

While the causes of poverty are complex and varied, what do you feel are a few of the biggest contributors in creating the long-term poverty that exists within your community or region?

Tom Carew: It is the economy of Central Appalachia that drives poverty. The outflow of our young people to the urban centers is primarily driven by the job market. While our political and economic development leaders work hard to attract industry to Rural Appalachia, it is an uphill battle. Some folks from my hometown of Morehead, Kentucky drive over 140 miles per day to jobs in Lexington or Georgetown, Kentucky.

Tom Carew: It is the economy of Central Appalachia that drives poverty. The outflow of our young people to the urban centers is primarily driven by the job market. While our political and economic development leaders work hard to attract industry to Rural Appalachia, it is an uphill battle. Some folks from my hometown of Morehead, Kentucky drive over 140 miles per day to jobs in Lexington or Georgetown, Kentucky.

Recruiting teachers to McDowell County is difficult, and even if they are recruited, affordable housing for young teachers is not available.

-Tom Carew

The four lane roads have helped make this possible, but isolation is still evident in towns like Welch, WV, a two hour drive to the nearest four lane highway. As the 2013 school year began in McDowell County, WV, they were 50 teachers short! Due to its isolation, recruiting teachers to McDowell County is difficult, and even if they are recruited, affordable housing for young teachers is not available.

Pinky Clifford: I think our economic corridors have limited growth and access to landowners so that they are unable to live on their own land. We constantly go elsewhere to purchase goods and services that could be provided right here to create jobs, financial stability, economic development, larger schools, adequate health care, and safe communities. One of the biggest contributors in dealing with long-term poverty is the huge growth spurt that we’ve had. Over 50 percent of our population is under the age of eighteen. We have never had a lot of economic opportunity offered to us until the last twenty-five years or so.

Bill Bynum: One of the biggest contributors to long-term poverty includes a systemic lack of access to opportunity structures for the children and families that live in economically distressed communities. Poor communities are less likely to have high quality schools and access to good jobs than communities of affluence.

Selvin MaGahee For many of the unskilled and/or uneducated workers in my area, the minimum wage does not afford them a fair opportunity to take care of themselves and their families, even when working two jobs. Furthermore, some are locked out of the job market because of criminal records, often for petty offences that receive unequal treatment in the judicial system based on race or ethnicity.

Ann Cass: One of the biggest contributors to long-term poverty is companies paying poverty wages rather than a living wage. The low wages mean that our talented craftsmen often migrate north where they can make three or four times that amount but at the cost of leaving their families and community behind. With low-wages people also succumb to pay day loans and title loans, which keep them in economic bondage.

Bill Bynum: The relationship with a depository financial institution matters greatly. Low-income families with an account at a depository are more likely to own assets than families of similar means without an account. Additionally, in low-income neighborhoods, there is a strong relationship between the presence of a branch and the origination/cost of mortgages. Responsible financial institutions provide families with the tools needed to accumulate assets that pave the way for families to get ahead. In communities mired in the cycle of long term poverty, the presence of sustainable, responsible financial institutions is often absent relegating services to instead be provided by high cost, wealth stripping entities.

Tom Carew: In Central Appalachia, low-wages make it near impossible to access traditional financial markets because of strict underwriting.

Ann Cass: Our cities refuse to provide affordable housing, even though they want low-income people to maintain their golf courses, clean municipal buildings, work in restaurants and hotels. In Hidalgo County, working families have no other choice than to live in a rural colonia (shantytown). There is no planning and zoning enforcement in the unincorporated areas of the county where most of the 1,200 colonias are. This means no garbage collection, street lights, parks and recreational areas. There is no building code enforcement. Public transportation is practically non-existent, health care is perceived as a privilege, not a right, and people die of diseases that in this country they should not die of. Because poverty has existed here for so long, in a racist system where people of color do not have access to resources, decision making, or leadership, many have developed a learned helplessness of “this is the way it has been, is, and will be forever.”

How much can a home take with such severe overcrowding?

-Pinky Clifford

Pinky Clifford: In all my years on this planet, I have seen and heard about economic initiatives that have come and gone doing little to address the long-term poverty.

With your experience working in these regions, what are some of the changes you have seen in the nature and level of poverty over the past few decades?

Pinky Clifford: Conditions are worse on Pine Ridge. With a larger population and not many more jobs, homes or rentals, and more quick fix trailers, you have more wear-and-tear on everything: stress on families (substance abuse, suicide, domestic violence), road systems, hospitals, schools, homes – how much can a home take with such severe overcrowding? When everything becomes worn you think of replacement, and when you don’t have the resources for replacement, then the community degenerates and the veil settles in.

Ann Cass: The colonias now have some infrastructure; paved streets, potable water, either public sewer or septic fields, but they still need street lights, parks, garbage collection, and drainage systems. After Hurricane Dolly, we were building in 10 colonias that were under water for more than 120 days!

Although finding a decent paying job in the area is still a challenge, more and more children from the colonias are going on to college. School districts are beginning to replace ESL classes with dual language enrollment, teaching classes in English and Spanish from k-12 grades. These schools are graduating students who are fluent in both languages.

Selvin MaGahee Over the past few decades I have seen many substantial changes for the better. Most of the flagrant acts of racism and discrimination, often supported by public institutions, have gone away. Laws have been enacted that make such acts illegal, although in many cases, acts of discrimination have become more subtle and much more sophisticated. This has been evident in the past couple of years through the dismantling of some of the long established protections including voting rights, government contracting, educational opportunities, and so on.

Tom Carew: Life without question is better in the physical sense. Water, sewer, hospitals, health care, highways, school facilities, and reasonably priced utilities are all much better than they were 50 years ago. On the other hand, high school dropout rates remain high in many counties, and persistent unemployment and low-paying jobs can be seen throughout the region. Unemployment in the coal fields is high.

Despite robust profitability, bank branches have closed at high levels –disproportionately in high poverty areas.

-Bill Bynum

Are we better off than 50 years ago? Most definitely – but as we look at Central Appalachia as a region, we remain at the bottom when compared to the rest of these great United States.

Bill Bynum: One phenomenon on which we have been paying close attention is the proliferation of bank deserts. Despite robust profitability, bank branches have closed at high levels –disproportionately in high poverty areas. In Mississippi alone, 1,031 of 1,679 ZIP codes are bank deserts.

When banks decide to leave certain markets, particularly markets with a substantial population of low-income residents, leaders face a continuum of choices. At one end, banks can work to find responsible, sustainable alternatives through partnerships with Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) and nonprofit organizations. At the other end, banks can simply export the community assets held in the branches slated to close to more affluent communities without consideration of the residents left behind. We’ve seen both approaches applied by banks – it remains to be seen whether or not the financial sector in our region can embrace a habit of meaningful collaboration.

What are the ramifications of persistent poverty for affordable housing provision within your community?

Bill Bynum: Within the Mid South’s persistently impoverished communities, and particularly those with high populations of African Americans, high cost lending was particularly prevalent during the early part of the last decade. Mississippi provides a good case study. In 2007, black households in Mississippi received approximately 10,000 mortgages. Four out of 10 mortgages to black households in Mississippi were classified as high cost loans. The same year, white Mississippi households received 36,000 mortgages, of which 2 out of 10 were classified as high cost.

A disproportionate amount of substandard housing is located in low-income communities

-Selvin McGahee

In 2012, mortgage originations for black households were just over half the number of mortgages originated in 2007. High cost lending dropped drastically; however, prime loan lending to African American households remained significantly below 2007 levels. For white households, high cost lending also dropped, however the drop had been more than made up for by increased levels of prime lending with both prime and total mortgage originations surpassing 2007 levels.

Selvin MaGahee Persistent poverty makes it very difficult for people in the rural south to improve their living conditions. A disproportionate amount of substandard housing is located in low-income communities. The economic downturn that began 6-8 years ago has made fewer resources available and decreased the availability of affordable housing. Housing policies at the federal, state and local levels have also had a negative impact on affordable housing. Things are not getting better; in fact they are getting worse.

Tom Carew: Central Appalachia has its urban centers: Morgantown, Charleston, Knoxville, Kingsport, Johnson City, Bristol, Chattanooga, which are, relatively speaking, better off than the surrounding rural counties. But decent housing has always been about affordability. The poorer the region, the harder it is to afford a decent home.

Selvin MaGahee Housing costs are typically the largest single item on a household budget. The initial move-in costs, security and utility deposits, or down payments for homeowners, are often insurmountable hurdles for most people in poverty. Without some type of subsidy these costs easily consume 50 percent or more of the monthly income for someone in poverty. Circumstances become even more extreme with any crisis such as the loss of employment, extended illness, accidents, and so on, often leading to overcrowded extended families or even homelessness. Poverty affects the quality of housing that can be afforded, and most substandard housing, both rented and owned, is occupied by people in persistent poverty.

Bill Bynum: The effects of persistent poverty following the Great Recession point to a widening of gaps within the Mid South that are already too far apart, especially given the relationship between homeownership and wealth accumulation.

Ann Cass: We do a before and after survey of our home owners to measure our success in improving their physical and mental health, children’s progress in school, sociability, and accrual of financial wealth with a new home. It is clear that substandard housing contributes to negative outcomes for all of the above, while new affordable housing make a huge positive difference in the quality of life.

Persistent poverty leads to higher rates of poverty, sicker people due to substandard housing (we are the asthma capitol of the country), separated families, and mental health problems, such as depression and drug and alcohol abuse. The worst result of all this is a sense of hopelessness it brings.

Pinky Clifford: Inadequate financial and management skills results in a lack of motivation to want to move forward no matter where you are in life, as does a lack of sufficient or better housing to create new and safer communities. When we talk about safe communities you have to have adequate services to support the community.

What strategies, solutions, or policies would you recommend to reduce poverty and long-term poverty in your community?

Tom Carew: The War on Poverty has had many successes in Central Appalachia as well as throughout the rest of the US, but our region along with the Delta, Native American lands, and the colonias continue to be the poorest places in America. The regions need to convene and come up with a strategy to collectively move us off the bottom! It is certainly time for us to move these regions forward. Obviously, this is not just a housing issue; it involves all aspects of life and endeavors in the regions. What has seemingly worked for the rest of America has not worked as well for us. How do we create and or shape federal and state policies to better serve the regions and provide the changes we need? This will take academics, activists, economic experts, and community developers.

Selvin MaGahee We must acknowledge and understand that there are distinctly different needs in urban and rural communities. Yet, often the policies and programs implemented at the federal or state level are designed with one-size-fits-all approach. Rural communities are not typically entitlement communities for federal funds like CDBG or HOME, they have to compete – often against the larger urban areas that have more resources and expertise.

It is extremely important to design the strategies and policies from a rural perspective. We should make every effort to reduce housing costs, or at least reduce the vast number of households that are cost-burdened. Our state and federal governments should strive to create more affordable housing rather than dismantling successful programs that have worked well for years to help address the problems.

Bill Bynum: Congress and the Administrations should direct 10 percent of any agency’s appropriated funding to counties and parishes that have experienced poverty rates in excess of 20% for 30 years. Enhancing the capacity to help these residents and communities represents one of the most effective strategies for attacking persistent poverty. Investment in CDFIs that have demonstrated track records of bridging the banking gap by connecting underserved populations to safe, affordable financial services is a proven model that builds ladders of opportunity.

Over the last year, HOPE has either experienced, or worked with other credit unions and CDFIs that have experienced a range of responses from banks when closing branches. On one end of the spectrum, one bank that left a community donated a branch to a community development credit union and assisted with transitioning customers from the bank to the credit union. On the other end of the spectrum, a town’s only bank closed its branch and placed a restrictive covenant on the facility that prohibited its use by another financial institution. The Community Reinvestment Act should be strengthened to create more incentives for the first scenario to occur and significant disincentives to prevent the second.

Ann Cass: We are working to help the economic development corporations understand that they have to change the paradigm of what they consider to be economic development. Bringing in new companies, with most of the jobs paying minimum wage, is not economic development.

It is clear to me that we absolutely need to focus on mixed-income neighborhoods and affordable housing. We have to make it possible for people to get out of the colonias. We are watching carefully as cities are working on their development plans. We see they are requiring larger homes in an effort to keep low-income families from living there. We see NIMBYism taking place where housing authorities are prevented from developing units in neighborhoods that are not already blighted with poverty. Those are policies that we are working on.

The bottom line is that we need more affordable housing, rental and ownership. We have 3,800 families on our waiting list and the only thing preventing us from significantly decreasing the list is lack of funding. Building a new house is of course not the only thing needed. I do believe that as housers we need to continue working with the families providing them as many resources from the community that we can. It is our experiment, for better or worse, at getting families from poverty to prosperity.

Pinky Clifford: Federal and nonfederal agencies, corporate entities, foundations and organizations (both public and private), and individuals who want to make change need to look at the map showing poverty in the United States and concentrate on the poorest areas. Combining their resources they could focus on helping us help ourselves. By that, I mean that consultation with leadership would let all of the above know what we need to re-capture the spirit of self-sufficiency. The solution on our side is not simple. Any underserved area has to do a lot of homework in its own strategic planning to assure any entity that we are serious.

Poverty tends to mask the positive in a community. We are proud of our tribal programs and our accredited college, our chamber of commerce, our schools, our nonprofits and other faith-based and community organizations who work hard to provide much needed services to our communities. However, this is a large Reservation and they can’t do it all. We want out of the dark area on the map.

More on Persistent Poverty

To read the contributors’ full interviews, please visit: www.ruralhome.org/revisitingpoverty

This story appears in the 2014 Special Edition of Rural VoicesDouglas County, Oregon is arguably one of the most beautiful places anyone could hope to live. The icy cold waters of the North Umpqua rush headlong down from their headwaters at Lake Maidu in the Cascade Mountains. The North Umpqua crashes headlong into Little River at Glide forming the only head-to-head colliding rivers in North America. Tall evergreen forests give way to grass-covered, rocky hills of madrone and scrub oak. Outside Roseburg, the North and South Umpqua meet and join to make their way to the coast. Douglas County stretches from Central Oregon to the Oregon Coast and just a bit bigger than the state of Connecticut. For all the beauty surrounding the residents in Douglas County, life here can mean facing some ugly realities. Jobs are scarce. The median income is among the lowest in the state, and unemployment persists at higher levels than most of the state – and much higher than the national average. Resources, too, are limited by the rural nature of the county, and county budgets have been severely curtailed by the loss of timber revenues.

This story appears in the 2014 Special Edition of Rural VoicesDouglas County, Oregon is arguably one of the most beautiful places anyone could hope to live. The icy cold waters of the North Umpqua rush headlong down from their headwaters at Lake Maidu in the Cascade Mountains. The North Umpqua crashes headlong into Little River at Glide forming the only head-to-head colliding rivers in North America. Tall evergreen forests give way to grass-covered, rocky hills of madrone and scrub oak. Outside Roseburg, the North and South Umpqua meet and join to make their way to the coast. Douglas County stretches from Central Oregon to the Oregon Coast and just a bit bigger than the state of Connecticut. For all the beauty surrounding the residents in Douglas County, life here can mean facing some ugly realities. Jobs are scarce. The median income is among the lowest in the state, and unemployment persists at higher levels than most of the state – and much higher than the national average. Resources, too, are limited by the rural nature of the county, and county budgets have been severely curtailed by the loss of timber revenues.

Tom Carew: It is the economy of Central Appalachia that drives poverty. The outflow of our young people to the urban centers is primarily driven by the job market. While our political and economic development leaders work hard to attract industry to Rural Appalachia, it is an uphill battle. Some folks from my hometown of Morehead, Kentucky drive over 140 miles per day to jobs in Lexington or Georgetown, Kentucky.

Tom Carew: It is the economy of Central Appalachia that drives poverty. The outflow of our young people to the urban centers is primarily driven by the job market. While our political and economic development leaders work hard to attract industry to Rural Appalachia, it is an uphill battle. Some folks from my hometown of Morehead, Kentucky drive over 140 miles per day to jobs in Lexington or Georgetown, Kentucky.

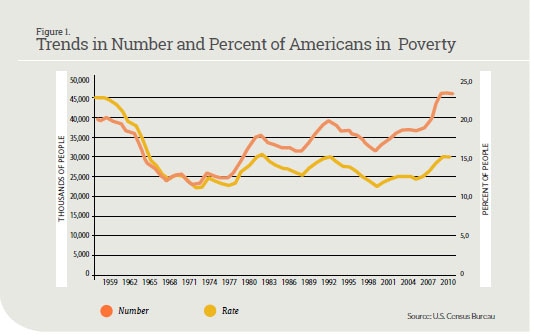

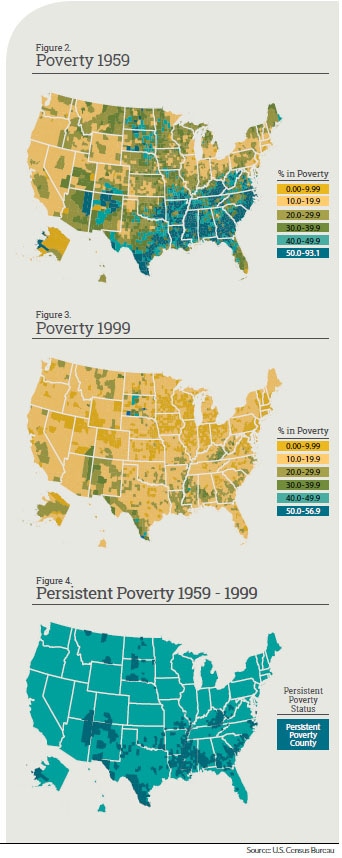

What is missing from Figure 1 is the vast differences in poverty rates across the country. For example, while the overall poverty rate in 1959 was 22 percent, Figure 2, which depicts poverty rates at the county level from the 1960 Decennial Census, shows that in much of the rural South and Native American territories poverty rates exceeded 50 percent. It was this level of deep poverty that then-Senator John F. Kennedy witnessed during a campaign stop in West Virginia in his 1960 bid for the presidency, and subsequently shaped his domestic agenda and that of President Johnson.

What is missing from Figure 1 is the vast differences in poverty rates across the country. For example, while the overall poverty rate in 1959 was 22 percent, Figure 2, which depicts poverty rates at the county level from the 1960 Decennial Census, shows that in much of the rural South and Native American territories poverty rates exceeded 50 percent. It was this level of deep poverty that then-Senator John F. Kennedy witnessed during a campaign stop in West Virginia in his 1960 bid for the presidency, and subsequently shaped his domestic agenda and that of President Johnson.