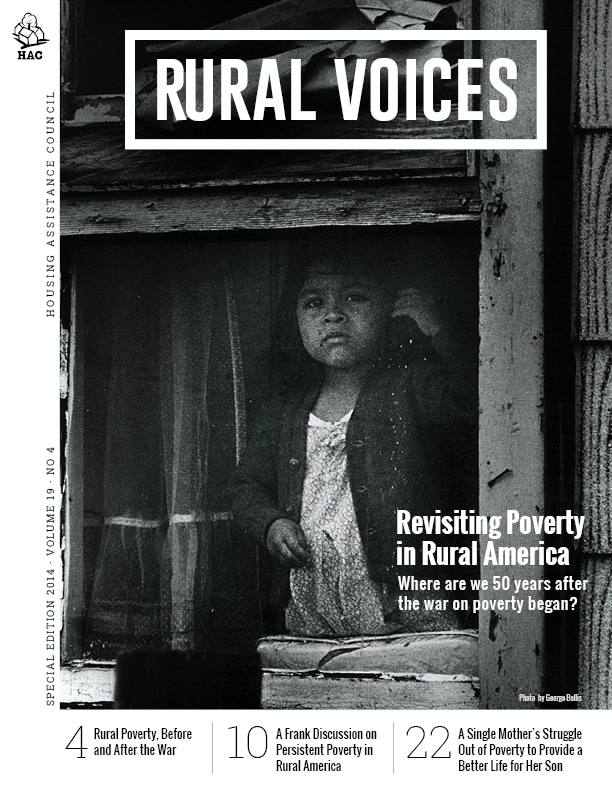

Revisiting Poverty in Rural America

Rory Doyle / There Is More Work To Be Done

Rory Doyle / There Is More Work To Be Done

By Stacey Howard, Dream$aver IDA Program Director, NeighborWorks Umpqua

This story appears in the 2014 Special Edition of Rural VoicesDouglas County, Oregon is arguably one of the most beautiful places anyone could hope to live. The icy cold waters of the North Umpqua rush headlong down from their headwaters at Lake Maidu in the Cascade Mountains. The North Umpqua crashes headlong into Little River at Glide forming the only head-to-head colliding rivers in North America. Tall evergreen forests give way to grass-covered, rocky hills of madrone and scrub oak. Outside Roseburg, the North and South Umpqua meet and join to make their way to the coast. Douglas County stretches from Central Oregon to the Oregon Coast and just a bit bigger than the state of Connecticut. For all the beauty surrounding the residents in Douglas County, life here can mean facing some ugly realities. Jobs are scarce. The median income is among the lowest in the state, and unemployment persists at higher levels than most of the state – and much higher than the national average. Resources, too, are limited by the rural nature of the county, and county budgets have been severely curtailed by the loss of timber revenues.

This story appears in the 2014 Special Edition of Rural VoicesDouglas County, Oregon is arguably one of the most beautiful places anyone could hope to live. The icy cold waters of the North Umpqua rush headlong down from their headwaters at Lake Maidu in the Cascade Mountains. The North Umpqua crashes headlong into Little River at Glide forming the only head-to-head colliding rivers in North America. Tall evergreen forests give way to grass-covered, rocky hills of madrone and scrub oak. Outside Roseburg, the North and South Umpqua meet and join to make their way to the coast. Douglas County stretches from Central Oregon to the Oregon Coast and just a bit bigger than the state of Connecticut. For all the beauty surrounding the residents in Douglas County, life here can mean facing some ugly realities. Jobs are scarce. The median income is among the lowest in the state, and unemployment persists at higher levels than most of the state – and much higher than the national average. Resources, too, are limited by the rural nature of the county, and county budgets have been severely curtailed by the loss of timber revenues.

Chriset came to Roseburg (population about 21,000), the largest town in Douglas County, in 2011 with her 13 year old son, Gabe. Chriset was following her mother and sister who had moved to the area several years earlier. Driving into town in her dilapidated Toyota Camry, Chriset managed to find a temporary home for the two of them in the spare bedroom of a friend in tiny Sutherlin, 11 miles north of Roseburg.

Chriset came into town with no money, but a lead on a job at a Roseburg non-profit. She landed the job, and with her new salary – the most money Chriset had ever made – Chriset managed to rent a tiny one-bedroom attic apartment for her and Gabe. The apartment was freezing in winter and the baseboard heat was so expensive they rarely used it. Even with her new job, Chriset found the apartment difficult to afford. To conserve energy, Chriset would turn off her power at the main box every day before she left for work. With her new job, Chriset lost the food stamps that had been part of her food security. Chriset had no internet (and has never had cable TV), and made all of her meals at home from basic ingredients. Still, when Chriset’s car died after 3 months in Roseburg, she felt she could not afford a new one, and the old one didn’t seem worth repairing. Chriset says, “I can’t imagine how people can afford a car. I don’t have $200 extra in my budget each month!”

Chriset started bicycling to work, and Gabe (like most kids his age) was able to get around by bussing to school and walking or biking everywhere else. Chriset remembers their living situation was “sub-par”. After a few months at her new job, Chriset learned of a landlord who was willing to rent at a reduced rate to an employee at the non-profit where she works. Chriset applied for the rental, and she and Gabe moved into a spacious 3 bedroom historic house only a half a block from her job. To afford the new home, Chriset had to have a roommate, but she also had a garden, and Gabe had his own room. The new house, though roomier, was also old, drafty, and difficult to heat. Chriset wanted to quit moving around – she had moved so many times and twice had lost her rentals when the landlords went into foreclosure. Chriset wanted a home of her own.

In 2012, Chriset applied for an Individual Development Account (IDA) through another non-profit. The Oregon IDA Initiative provides a matched savings program for low-income individuals to help them purchase assets with the hope that they will become more financially stable and eventually move out of poverty. One of the eligible uses of the funds is the purchase of a first home. Chriset had to save $1000 of her own to receive $4000 in matching grant funds ($3000 from state funds and an additional $1000 from the federal Assets for Independence program). Chriset had savings accounts before but had never been able to build a balance. Through the IDA program, Chriset was saving money for the first time.

In addition to saving money, financial education helped Chriset improve her credit score and start tracking her expenses and budgeting using online resources. She also took home buying classes. Yet, Chriset was having a very difficult time finding anything suitable to purchase in her price range. She needed something close enough to her job and Gabe’s school that they could make do without a car. Chriset also needed a large yard with enough sun to continue growing her vegetables and fruits – and she wanted to be able to plant fruit trees. Chriset’s younger brother, a computer programmer in Seattle, offered to loan her additional money to make a deal work, and Chriset doggedly kept up her search. Finally, she found a property that was “distressed” – the current owner, an investor, needed to get rid of the property quickly because of cash flow problems. It met much of Chriset’s criteria; large lot, room for trees, two bedrooms, a big kitchen. A huge bonus for Chriset was a smaller cottage that she could rent out to help pay her mortgage. And, the price was right, at about $95,000. The house needed too much work to finance, but Chriset was able to convince the owner to carry a contract because of her ability to make a down payment.

In the late summer of 2013, Chriset and Gabe moved into their new home. Chriset immediately started a new IDA for some of the home repairs she would need. She shopped the local recycled building materials store for supplies, borrowed tools, and traded labor with friends. Chriset learned to replace windows, caulk, paint, and landscape. A whiz at bargaining, Chriset talked a local tree service into dumping wood chips in her yard for mulch. She planted fruit trees and her garden (with a few flowers for looks). She became a landlord and manages to pay half her monthly mortgage through the rental income. She has insulated, upgraded the electrical, and refinished her wood floors. While her home continues to be a “project house” – and she still is cold in the winter, at least until she saves enough for a new heating system – Chriset loves her home. “I get to paint my walls, and I don’t have to worry about having to move. I will have the mortgage paid off in 6 more years, and then I will start paying off my brother, but every month I know the money I am paying is going to benefit me in the future.”

Gabe walks 3 blocks to the local high school. Now entering his sophomore year, Gabe is earning A’s and B’s for the first time in his life. Says Chriset, “I don’t know for sure what is different now for Gabe…he’s a teenager, so you never know. But I am so thrilled with how he is doing.” Chriset and Gabe still eat at home, and their only modes of transportation are bicycles and their own two feet. Chriset says even if she had the money to buy a car, she probably wouldn’t until her student loans and loans for the house were paid off. Gabe gets insurance through the Oregon Health Plan, so Chriset doesn’t have to worry about his medical care, but just in case, she makes sure both of them stay healthy. Life hasn’t been easy for Chriset, but she says, “I like my life. Things have been rough, but they are getting better. Sometimes, if one more thing wasn’t totally OK…one little thing can devastate a family. Right now, I am happy.” Chriset’s face glows, probably from her healthy lifestyle of eating fresh, simple foods and bicycling many miles every week. But probably, it also glows because Chriset knows she has a home, one no one can take away.

Stacey Howard has lived and worked in rural Oregon for most of her life. She is currently the Director of the Dream$avers IDA Program at NeighborWorks Umpqua in Roseburg, Oregon.