Always Improving, One Misstep at a Time

This story appears in the 2015 Spring Edition of Rural Voices

This story appears in the 2015 Spring Edition of Rural Voices

“I have not failed. I have just found ten thousand ways that won’t work.” Thomas Edison was no stranger to failures, but he took a healthy approach to mistakes.

By Nick Mitchell-Bennett and Kathy Tyler

Strange as it may sound, we like making mistakes. Often we learn more from mistakes than doing it right the first time. Since we must be risk-takers we have ample opportunity to fail. We must take risks to help those we serve gain access to affordable housing, affordable financing, education, or any of the hundreds of things we do in our work. Like Thomas Edison, we’ve learned not to be afraid of mistakes but to enjoy the teaching moments they offer. The trick is learning the best alternative for the next try (since some of us cannot afford Edison’s 10,000 ways that won’t work)!

We made plenty of mistakes together when we formed the Texas 502 Packaging Collaborative . We watched other groups in other states create these partnerships and we wanted to replicate the partnership in Texas to increase the number of USDA Section 502 Homeownership loans and increase revenue for participating organizations.

Our two organizations, Community Development Corporation of Brownsville (CDCB) and Motivation, Education and Training, Inc. (MET), have strong track records. Collectively we build and finance hundreds of homes each year, develop multi-family projects, and improve migrant farmworker housing. We educate youth and farmworkers, and launch them into new professions. We run a real estate company and Head Start programs collectively.

So when we set out to form the 502 Collaborative, we assumed it would be an easy, natural next step. We assumed wrong.

Too many moving parts influenced by a range of decision makers not in our control meant projects more at-risk for what might go wrong.

Although partnerships can be fraught with difficulties, we have had some success and the Texas 502 Collaboration survives today. But we continue to struggle getting the scale we want and need.

After stumbling through this for a few years, we can name mistakes and summarize lessons learned in three points:

- Get the right partners.

- Build relationships with those partners.

- Do what you do best with the time you have.

Get the Right Partners

Our first mistake was selecting too few of the right organizations. We did not do enough homework to vet the organizations we selected. We thought we had the right groups, but we were wrong. We needed high-production groups, no matter their size. We needed organizations that understood how to find clients, had staff with the skill set to package loans, and that could manage risk. We needed organizations with understanding and willingness to add loan packaging as a core business. Too many were attracted to the possibility of generating income without understanding the staffing and work required to deliver the 502 package.

We convinced state leaders about the efficacy of the collaboration. We even successfully advocated for $500,000 from the Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs to reduce the 502 mortgages. But again, our homework was incomplete. We were not able to absorb the funding within its limited timeframe. Even worse, the USDA Section 502 funding that year came inconsistently through Congressional Continuing Resolution stops and starts, hurting our planned timeframe. Too many moving parts influenced by a range of decision makers not in our control meant projects more at-risk for what might go wrong. In our case, the dollars lined up, but the timing and partnerships did not.

Build the Relationships With Those Partners

After recruiting, training, and forming the Collaborative, we failed at fully communicating to the partners the next steps we needed to take for this collaboration to succeed. We tried to move too quickly! We held a successful 502 training, and then we went back to our daily work. The groups in the Collaborative needed more training. It was our responsibility to really help these organizations commit the time and money needed to package USDA loans. Nick went back to CDCB, making sure its staff were fruitful packagers. Kathy, having led the recruitment, returned her attention back to farmworker housing at MET. We handed over the collaboration to others’ leadership for implementation far too early. Initially we did not even notice that there were no successful packagers other than CDCB. We would have noticed if we had taken the time to listen to the groups and hear what more was needed for them to be comfortable with the packaging work.

Do What You Do Best With the Time You Have

In the nonprofit world, over-reaching is a common mistake. We tend to take on too much too often. Too often we think our organizations can do it all. This 502 Collaborative project meant recruiting groups, organizing trainings, raising funds, working with USDA and the state housing agency. In short, we underestimated the time we needed to invest. We should have brought others to the team earlier with time and dedication to see this through to the end. We had each set aside enough time to get the project started, but not enough time to get it to move smoothly and see it through.

Texas Community Capital still successfully runs the program. The two of us – the dreamers and instigators creating the Texas 502 Collaborative – failed to invest the time and attention to strengthen the Collaborative during its early stages. There were plenty of obstacles to come – uneven federal funding over the years, retirements and staff changes at every level and within every organization, and changing USDA regulations. A stronger framework would have helped.

Mistakes happen; we fail; but we need to learn and embrace these failures – then move on. A sign of physical fitness is how quickly one’s heart rate returns to its resting rate after stress. A sign of organizational fitness might be how quickly we learn from our mistakes and apply it to our next shot at success.

Kathy Tyler has worked in the affordable housing development and finance field for more than 35 years, in neighborhood, urban, rural, and farmworker settings. Currently and for this last decade she directs farmworker housing programs for Motivation Education & Training Inc. She still makes many mistakes. Nick Mitchell-Bennett has spent the past 25 years building and financing affordable housing trying to make as few mistakes as possible.

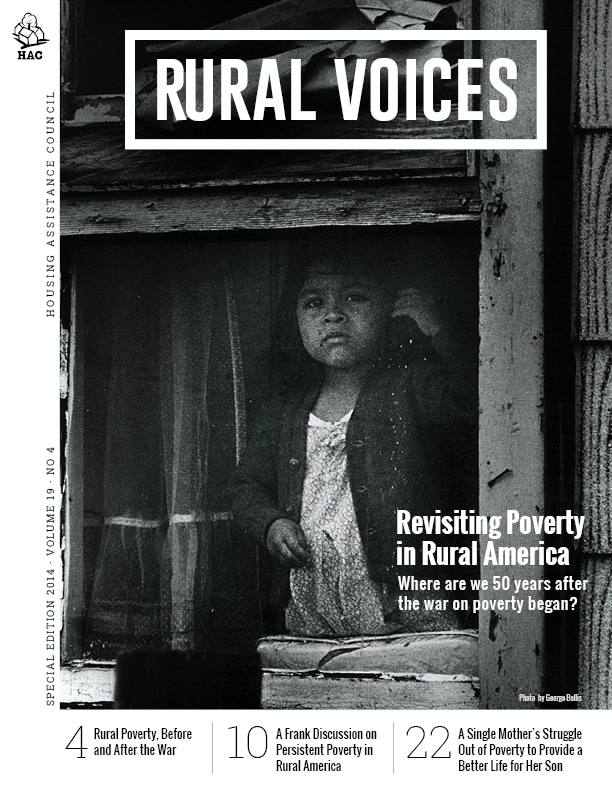

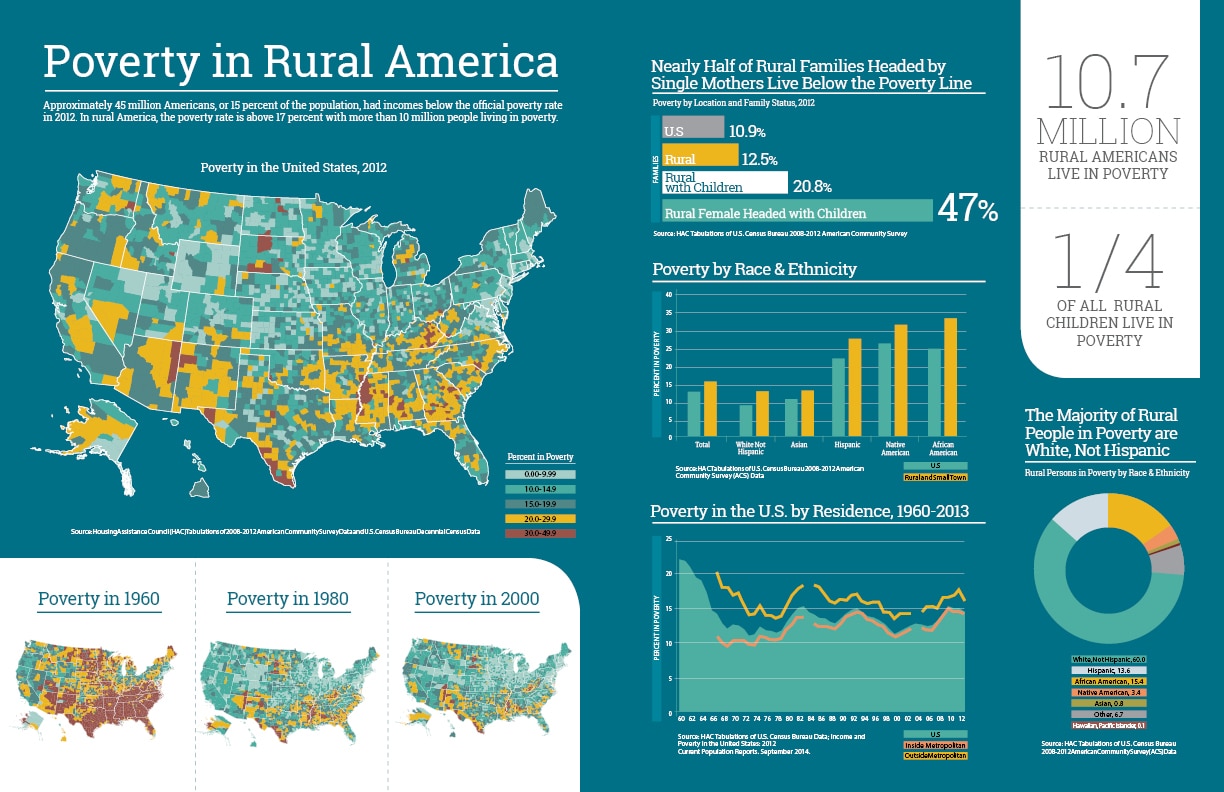

Poverty in Rural America

Poverty in Rural America

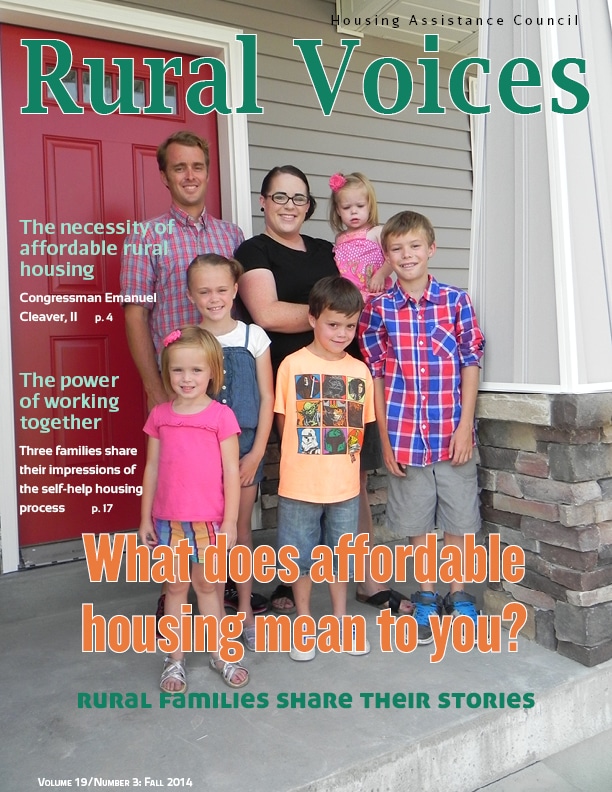

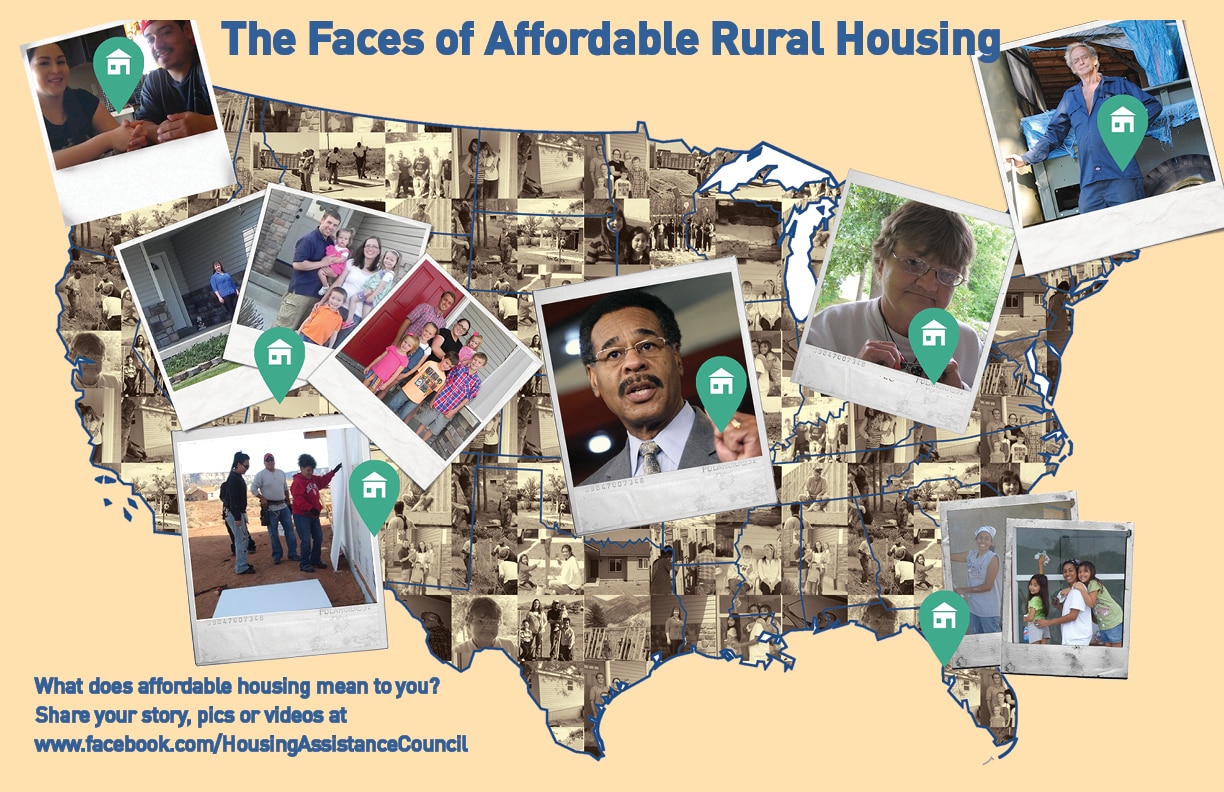

The Faces of Affordable Housing

The Faces of Affordable Housing