View From Washington

Congressman Emanuel Cleaver, II, shares his housing story and offers his views on housing across the country

by The Honorable Emanuel Cleaver, II, Missouri’s Fifth District

This story appears in the Fall 2014 issue of Rural VoicesOwning a home is part of the American dream. It’s a person’s private piece of paradise. The pride of home ownership often fosters not only a desire to take care of one’s personal property, but also an effort to protect the integrity and appearance of the surrounding neighborhood as well. Affordable housing is a key component to a vibrant, expanding, and prosperous community.

This story appears in the Fall 2014 issue of Rural VoicesOwning a home is part of the American dream. It’s a person’s private piece of paradise. The pride of home ownership often fosters not only a desire to take care of one’s personal property, but also an effort to protect the integrity and appearance of the surrounding neighborhood as well. Affordable housing is a key component to a vibrant, expanding, and prosperous community.

As a little boy, growing up in Waxahachie, Texas, my family and I didn’t have indoor plumbing until I was 7 years old. That’s when we moved up in the world, by moving into public housing. When a move into public housing is considered a monumental step up in the world, you can imagine the delirious euphoria that came years later, when we finally had a home of our own. My father worked three jobs, put my sisters, my mother, and I through college, and moved our family into the first home we ever owned. He still lives there today.

We all have our own personal stories, but the availability of, and access to, affordable housing for everyone, is a national concern as well. The buying and building of houses is a huge contributor to the vitality and viability of a community. Jobs are created or sustained as construction crews, real estate and other professionals, and business owners and employees are in high demand. The influx of tax dollars provides a solid foundation for public services including police, fire, and sanitation workers who help make a neighborhood safe, clean, and a quality place to live. Financial institutions make loans, restaurants sell food, and teachers begin educating our children. Affordable housing helps a community come alive. According to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), families and individuals living in Rural Development financed homes in the district I represent, Missouri’s Fifth District, see every dollar spent in the local economy multiply by six times.

So, I am asked all of the time, “What are elected officials doing in Washington to continue improving programs, increasing opportunities, and ensuring affordability for those in rural areas throughout our nation?” Sadly, a better question might be, “What are we doing in Washington at all?”

I say to you without hesitation – Not Enough! And some days, it seems, nothing is getting done at all. Except for arguing. The partisan back-biting, political bickering and agenda motivated maneuvering seem to go on forever. And it needs to stop. There are important issues on our plate. Issues that impact our families and our futures. Issues that need, and deserve, our serious attention right now.

Missouri’s Fifth District stretches all the way from the urban core of Kansas City east to the farms of Marshall. The distance is a whopping 90 miles, but the lifestyles seem even farther apart than that at times. My district truly represents a microcosm of this great nation, with not only urban and rural communities, but suburban ones as well. The needs of these residents vary greatly from region to region. Rural communities have different needs and different concerns than those in the other areas. And while it is my passionate belief that all residents of my district need access to affordable housing options, certainly my rural constituents have special and unique needs that need to be addressed as such.

As a Member of the House Financial Services Committee, and a Member of the Subcommittee on Housing and Insurance, I pay special attention to these issues and concerns. One important issue for rural communities, for instance, is flood insurance. Congress recently enacted the Homeowner Flood Insurance Affordability Act of 2013. This law protects people who have flood insurance from facing dramatic rate hikes. For constituents hit by premium increases they simply can’t afford, it provides relief in the form of a refund. The law also requires the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to get the affordability study to Congress that was supposed to be finished almost a year ago.

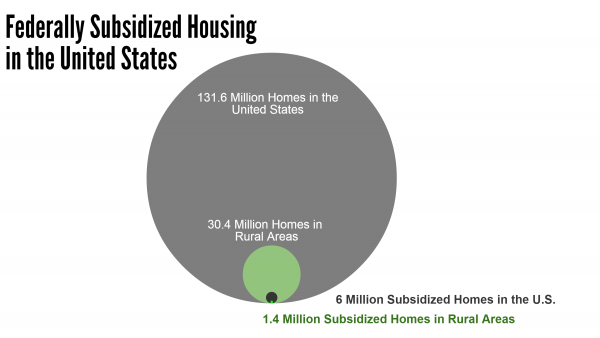

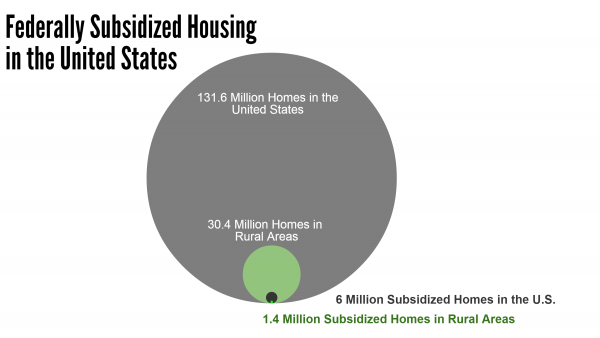

Source: HAC Tabulations of HUD and USDA data; National Housing Preservation Database

Source: HAC Tabulations of HUD and USDA data; National Housing Preservation Database

Folks living in rural areas are particularly well served by their local USDA offices. That agency plays a critical role in bringing the dream of home ownership within reach. For people who choose to live, work, and raise their families in this country’s strong rural communities, many have not only found that the programs focusing on housing loans have helped them buy, but have also vastly improved their quality of life. Other available options provide loans and grants for everything from hospitals, fire stations, and nursing homes, to funding for apartments for those with low-income or the elderly, schools, and housing for farm laborers.

There are issues and complexities that occur in a rural landscape unique only to those communities. The USDA, through Rural Development, has worked for more than half a century to understand those nuances and provide housing options that don’t exist outside of rural America. For instance, USDA’s loan program offers borrowers an opportunity for homeownership with no money down, and allows rural families to stay right where they are. I continue to believe moving rural housing programs under a freestanding FHA is not a move toward efficiency, as many in Washington contend, but one that sets rural communities back and leaves them stuck in the past.

Right now, in Missouri’s Fifth Congressional District, the numbers and dollar amounts for 502 Guaranteed loans active and being serviced in Jackson, Lafayette, Ray, and Saline counties, show an impressive amount of families utilizing the program. There are 1,691 loans totaling more than $170 million.

Affordable housing in rural America is not just a nicety, it’s a necessity. It must be available, accessible, and affordable for those who need it. And, make no mistake, I will continue fighting to make sure it’s just that.

Continue the Discussionby Matt Huerta, Neighborhood Housing Services Silicon Valley, CA, and Karen Jacobson, Randolph County Housing Authority and Highland Community Builders, WV

Continue the Discussionby Matt Huerta, Neighborhood Housing Services Silicon Valley, CA, and Karen Jacobson, Randolph County Housing Authority and Highland Community Builders, WV

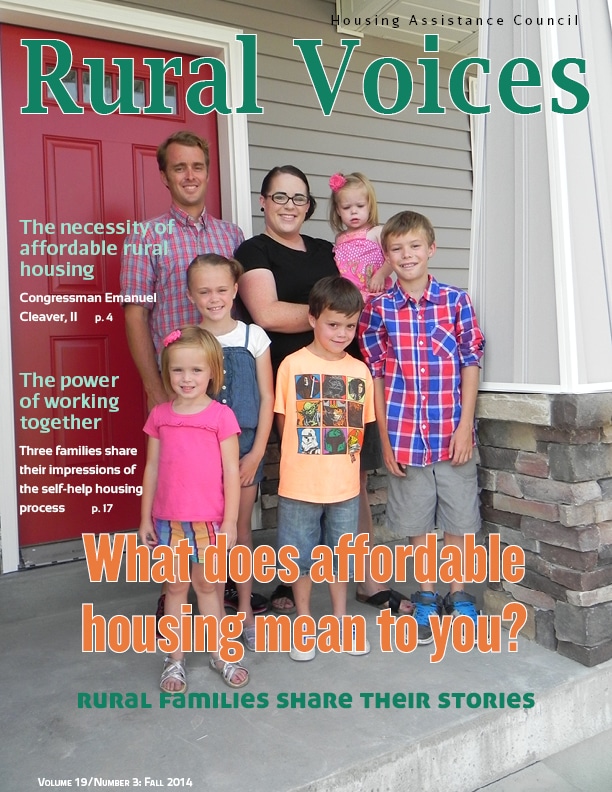

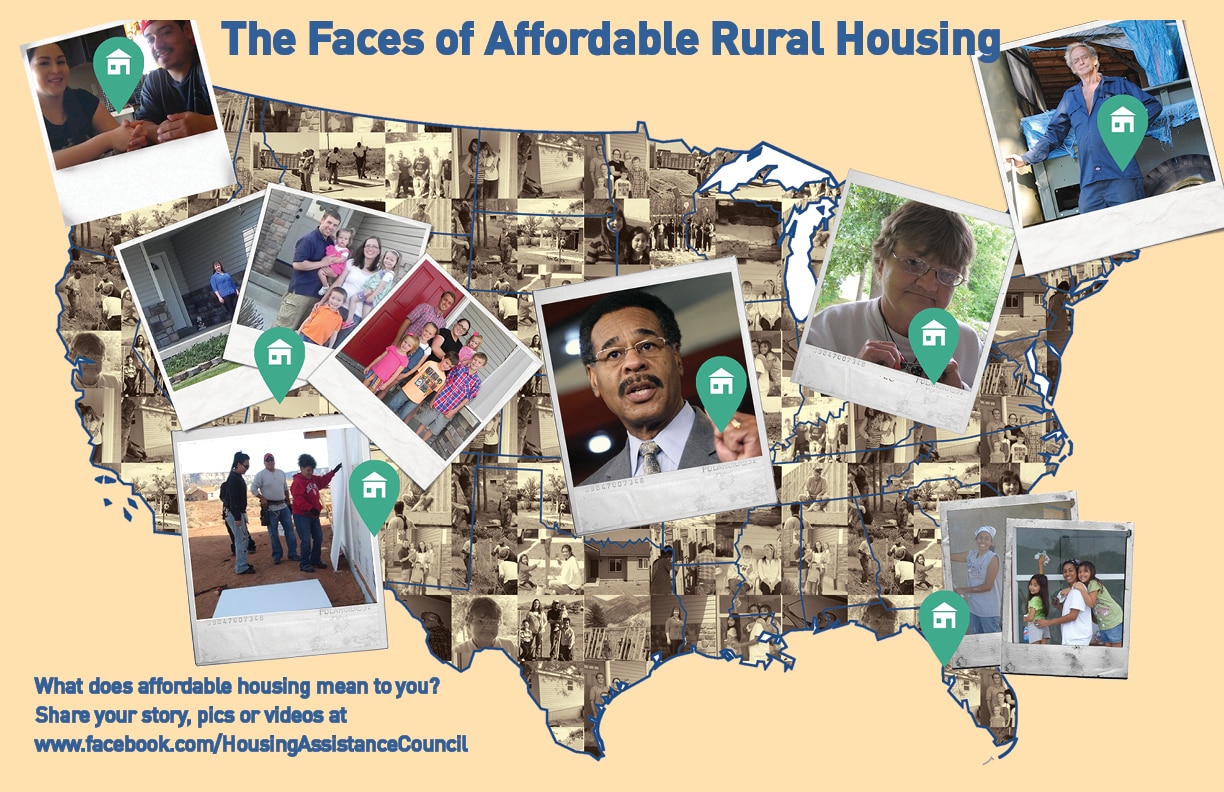

The Faces of Affordable Housing

The Faces of Affordable Housing