“I’m looking forward to spending whatever days I have, God bless me, in that house.”

– Kay Panteah, Zuni Tribal Member & Homebuyer

by BC Echohawk, National American Indian Housing Council (NAIHC)

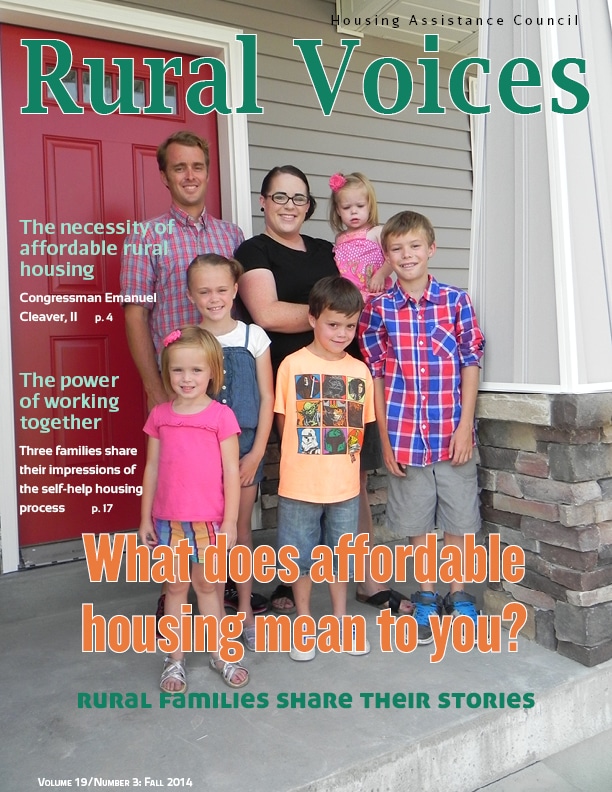

This story appears in the Fall 2014 issue of Rural VoicesThe Zuni Pueblo sits in the far western edge of New Mexico, forty miles away from Interstate 40, the major East-West corridor through the state. Kay Panteah is a tribal member and has lived in the area her whole life. The remote location has never factored into the 54-year old’s decision to remain in the community. Her parents were born and raised there, and she continued to live and care for her aging mother in the family home along with several siblings until their growing families created a need to find a place of her own. When the Pueblo of Zuni Housing Authority advised the single-mother of four that she had qualified for a rental home through their program, she never dreamed that that move would lead to owning her own home.

This story appears in the Fall 2014 issue of Rural VoicesThe Zuni Pueblo sits in the far western edge of New Mexico, forty miles away from Interstate 40, the major East-West corridor through the state. Kay Panteah is a tribal member and has lived in the area her whole life. The remote location has never factored into the 54-year old’s decision to remain in the community. Her parents were born and raised there, and she continued to live and care for her aging mother in the family home along with several siblings until their growing families created a need to find a place of her own. When the Pueblo of Zuni Housing Authority advised the single-mother of four that she had qualified for a rental home through their program, she never dreamed that that move would lead to owning her own home.

Kay Panteah speaks excitedly from the offices of the Pueblo of Zuni Housing Authority (ZHA) as she joins their Mortgage Coordinator Lorelei Sanchez to discuss her journey from renter to homebuyer. Given this opportunity to share the success of programs aimed specifically at Indians in rural communities, she’s eager to tell her story. Lorelei stands by, ready to fill in program information or nudge her memory as it becomes clear that these two women have created a strong bond in what has been a 14-year quest for stability and self-sufficiency.

“I LIVE FOR MY KIDS”

Kay describes her family: Oldest son Kardie Panteah is 36, and with his wife, has four children of his own, two adopted. He lives and works in the Pueblo of Zuni as a firefighter and EMT. Having mentioned an older daughter, Kay clarifies, without hesitation or judgment, that 26-year old Danii Panteah is transgender and her “special child.” Danii pursued post-secondary education in psychology and is currently working as a retail salesclerk. Twenty-three year old daughter Kimberly Kallestewa received a certification in Business Administration through Job Corps after finishing high school. She is looking for a job and expecting a child this fall. Kay’s youngest son, Jordan, 17, is finishing his senior year at Ramah High School near the Zuni Pueblo. They have all been high achievers academically, and were all chosen to participate in the local Boys’ State, a national program (with a girls affiliate program) of the American Legion that teaches high school students about how local, state and national government works. “I live for my kids,” says Kay. “So, what I do is practically just for them.”

USDA Rural Housing Service Administrator Tony Hernandez visits with the Panteahs

USDA Rural Housing Service Administrator Tony Hernandez visits with the Panteahs

It was this desire to provide a better home for her children that introduced her to affordable housing. A self-employed silversmith and retail salesclerk, Kay’s father died when she was only twelve. Her mother raised her and her siblings alone, and Kay never felt a need to leave the familiar community. She participates in the local traditional tribal and religious activities, and loves helping other families who also take part. However, she admits that times have changed, and safety has become a concern. Doors that once remained opened are now routinely locked. Young people with too much time on their hands and not enough to do roam the community well into the night. Security has stepped up and curfews have been enforced in the past few years. While these measures have helped, the community continues to change as outside media and values become more accessible and common.

In a situation not uncommon in Indian communities, Kay was living with her mother and some of her six siblings in the four-bedroom family home. She had been her mother’s primary caregiver, but as her older brother and sister’s families grew, she knew she would have to make a change. She applied to ZHA for a rental home, and in 2000 learned that she qualified for low-rental housing through them. “[T]he saddest thing was that I had to leave my mom.” says Kay. The rental home was eight miles away from her mother’s home, and she had never lived that far away. However, Kay’s children were all still living with her at this time, and knowing that the move would offer them more room made the change easier.

“I WISH I COULD…BUY A HOME”

In 2000, Kay moved with her four children into a four-bedroom home provided by ZHA. In addition to houses, ZHA also has apartment communities available to qualified low and moderate income renters. Kay was in this first house until 2010 when she moved to an adjacent home to allow for renovations to the housing authority’s inventory. During her time in the rental unit, due to some delinquency issues, it was recommended that Kay attend a financial literacy program that ZHA sponsored. This is where she met Lorelei Sanchez, ZHA’s Mortgage Coordinator and the instructor for their financial literacy classes. The women’s admiration for each other is evident as Lorelei explains that program, their meeting, and how Kay made such an impression on her, that retelling Kay’s story would lead to the Zuni program receiving the first American Indian-focused Self-Help program through the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Rural Development agency.

In explaining the financial literacy program, Lorelei notes the diverse people who attend those sessions, including renters, first-time homebuyers and members of the Zuni community whose goal is to create sound financial habits for their families. Spending and budgeting is discussed keeping in mind the reality of commitments to the traditional calendar that tribal members follow. Their year begins with the winter solstice and related celebrations. This, merged with the western calendar of holidays, can strain budgets, and attendees are taught how to prioritize and set goals and limits for their families. It was while discussing such goals, that Kay made clear her wish to own a home. The sincerity of this wish was not lost on Lorelei.

Given this opportunity to share the success of programs aimed specifically at Indians in rural communities, [Kay Panteah] is eager to tell her story

In 2011, the New Mexico Mortgage Finance Authority (NMMFA) was approached by USDA’s Rural Development program. They wanted a recommendation of a native community that might be in a position to utilize their Self-Help program. Eric Schmieder with NMMFA knew that Zuni was preparing to start a construction project and that they also had the capacity and resources needed to successfully qualify for the Self-Help funding. After Rural Development contacted the Zuni, and it was decided the housing authority would administer the program, ZHA director Michael Chavez tapped Lorelei to write the proposal. She still remembers her hesitation, as this was her first attempt at preparing a proposal. The Little Dixie Community Action Agency provided her technical assistance, however, and they recommended that Lorelei think of a client whose story she could tell. “[Kay] came to my mind just like that.” says Lorelei. Sharing Kay’s story became an important part of ZHA receiving their funding, and Lorelei admits she was amazed that they received the grant. In retelling the story she asks rhetorically, “And guess where I go knocking?” “My door,” Kay answers, and quietly repeats “My door. That was the happiest day of my life.”

“THE HOME I BUILT”

The agreement between Rural Development and the Pueblo of Zuni Housing Authority was signed in January, 2012. Lorelei helped Kay through the pre-qualification process for her new home, and the results came back positive with just a few outstanding debts. As luck would have it, the timing was in Kay’s favor, as it was tax season. Normally, she would have used her tax return for a belated Christmas for her children. This year, though, Lorelei spoke with Kay’s children and suggested they let their mother know that having a new home would be a better Christmas present. They did, and Kay agreed. Kay used that year’s refund to clear those debts, thereby allowing her to move forward with construction.

Kay Panteah and family working on home

Kay Panteah and family working on home

The groundbreaking was in May 2012, what was intended to be an eight-month process took over a year to see completion. Three houses were planned in the first round of construction, with each of them to be occupied by single mothers with families who were all former renters turned homeowners. Lorelei explains that as this was a new project for ZHA, there was a learning curve they worked through that caused some delays. Additionally, as can happen when working with construction in any federally-recognized Indian community, there were leasing issues related to building on tribal land that created obstacles. This issue caused a several-month delay in building. As soon as she was allowed, however, Kay was at the work site with her family, putting in the 600 hour sweat-equity requirement on her home. While technical work such as plumbing and electricity was contracted, the remaining tasks of framing, pouring concrete, digging trenches and putting up drywall are left to the homeowner. A construction supervisor was always at one of the three construction sites, providing training and direction to the families.

The process has empowered her, and she knows the other two participants feel the same

Kay had already gotten the commitment of her children and older grandchildren that they would help with the construction, but it was still an arduous process. They worked most days, despite the weather, and despite the fact that they lived ten miles away from their new home and sometimes didn’t have gas to make it to the site. On these days, they informed the construction supervisor so that he could go to another site and assist there. Following days that they missed, they would come to the site and work longer hours to make up for lost time. The other two families who were also working on homes helped her when they could, as she helped them when needed. Once the frame was up, however, Kay knew she would finish. It was then that she could “see” her completed home.

A low-point came when Kay was laid off from her retail job. In fact, all three of the women who were participating in the program were laid off in a short time span. Fearing this would affect her participation in the program, Kay went immediately to Lorelei to let her know. While this was discouraging news for all three women, Lorelei knew they had to move forward and encouraged Kay to begin the unemployment process immediately. She did, and in doing so was motivated to press on. Fortunately for Kay, she had the traditional skill of silversmithing to fall back on. She acknowledges that having completed the physical aspect of the project and overcoming all the obstacles that delayed construction, she has gained experience in how to properly finish a project of any kind; how planning and flexibility allow one to move forward. The process has empowered her, and she knows the other two participants feel the same way. Their work together has bonded them and created lasting friendships.

“MY NEW HOME”

In her position with the housing authority, Lorelei is able to see the bigger picture: success with the Self-Help program at Zuni will show the USDA that tribal communities can also manage the program and it will allow for more housing resources in Indian Country. For her first three participants, however, the benefits will be immediate and personal. The project came in under budget, so Kay’s mortgage payment will be lower than anticipated. Renters will be home owners, rent payments are now mortgage payments and reliance becomes self-sufficiency. Lorelei knows that Kay’s journey to home ownership began with the Financial Literacy class. Her rent payment had never been her priority, but after completing the class, Kay knew what she needed to do to realize the wish of owning her own home. The class gave her perspective and hope. It laid the foundation that allowed her to see what she could achieve.

As for Kay, on July 24 she received the keys to her new home. She admits it was an emotional process with ups and downs, but she also acknowledges that there were always people there who were willing to help and who did help. She remains grateful for the opportunity to participate in the project, and having built a home, she now looks forward to starting a small business in her community. “Never give up,” says Kay. “There’s always hope on the other side.”

The National American Indian Housing Council (NAIHC): The only national, 501(c)(3) corporation representing housing interests of Native people who reside in Indian communities, Alaska Native Villages, and on native Hawaiian Home Lands. NAIHC advocates for housing opportunities and increased funding for Native Americans; provides training and technical assistance to managers and professionals from Native housing programs; and conducts research related to Native housing issues and counseling programs, as well as loan products.

Housing Assistance Council

Housing Assistance Council

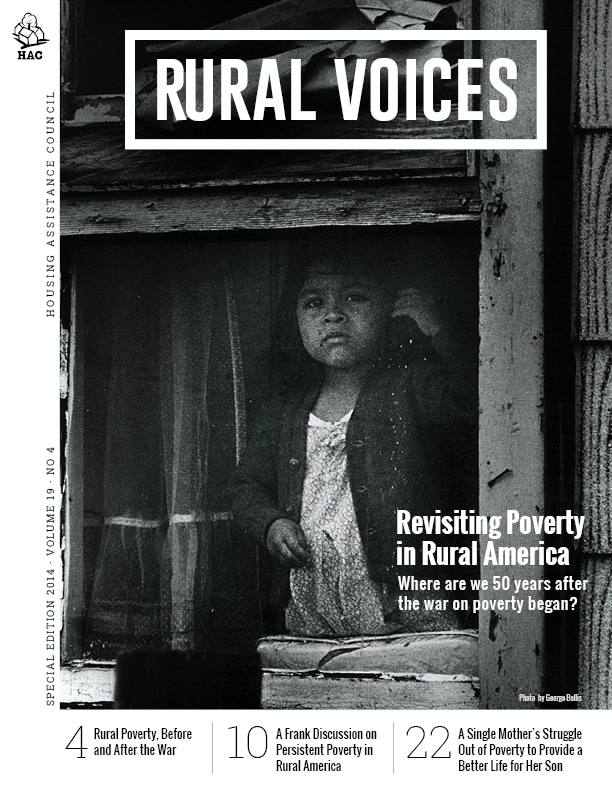

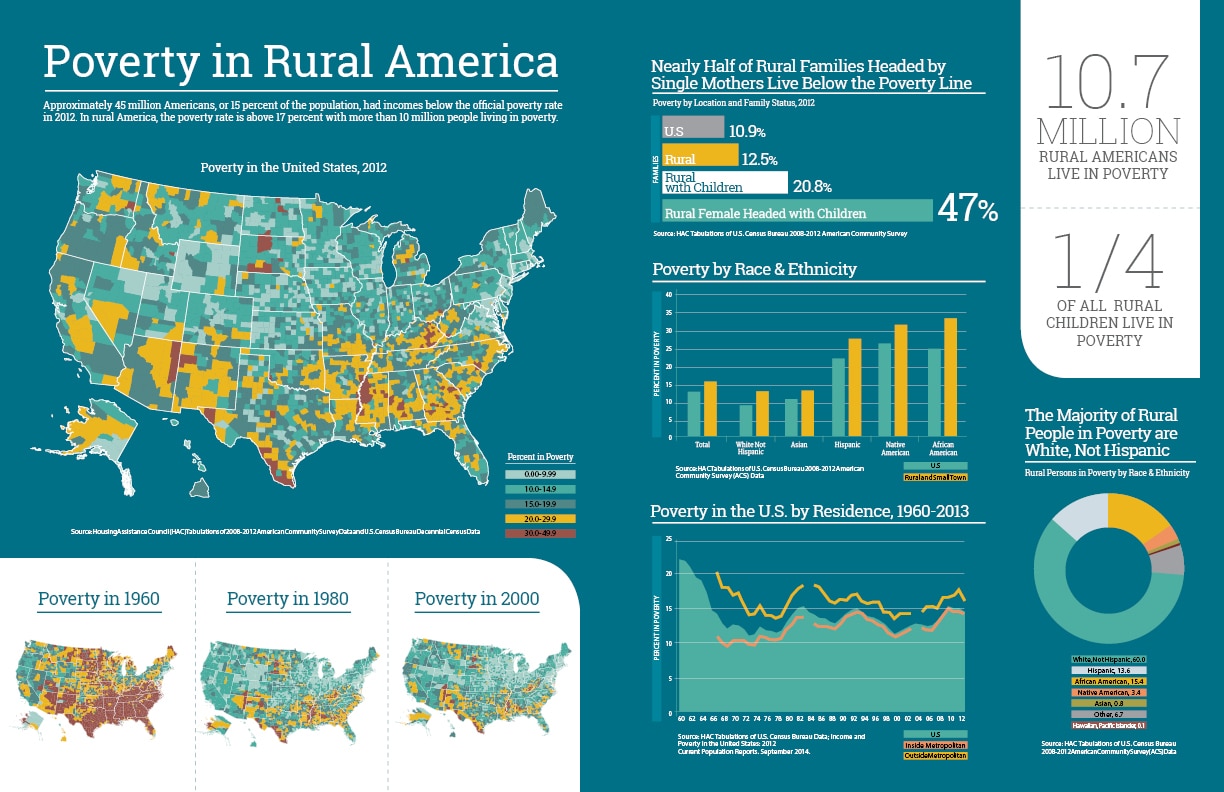

Poverty in Rural America

Poverty in Rural America

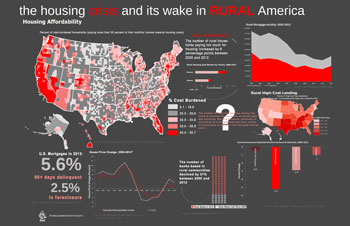

The housing crisis and its wake in rural America

The housing crisis and its wake in rural America