Is the Housing Crisis Over? And how did it impact rural America? – Shelia Crowley Responds

For more on this topic, read the July 2014 issue of

Sheila Crowley, Executive Director, National Low Income Housing Coalition What caused the home foreclosure crisis that came to a head in the fall of 2008 and precipitated the “Great Recession” is hotly debated. Explanations fall along predictably partisan lines. One side cites too much government interference in the marketplace, while the other side sees an unfettered marketplace allowed to run amok.

Sheila Crowley, Executive Director, National Low Income Housing Coalition What caused the home foreclosure crisis that came to a head in the fall of 2008 and precipitated the “Great Recession” is hotly debated. Explanations fall along predictably partisan lines. One side cites too much government interference in the marketplace, while the other side sees an unfettered marketplace allowed to run amok.

For more on this topic, read the July 2014 issue of

In 2008 the U.S. economy fell off a cliff. Depending on your perspective it either slipped or was pushed from that precipice by the housing markets. But after six years where are we? How were rural Americans impacted, and are there lingering effects from the crisis? Rural Voices assembled four of the most knowledgeable experts in the affordable housing world to help answer these complex questions and provide insights on how to improve rural housing conditions in the wake of the housing crisis.

Sheila Crowley, Executive Director, National Low Income Housing Coalition What caused the home foreclosure crisis that came to a head in the fall of 2008 and precipitated the “Great Recession” is hotly debated. Explanations fall along predictably partisan lines. One side cites too much government interference in the marketplace, while the other side sees an unfettered marketplace allowed to run amok.

Sheila Crowley, Executive Director, National Low Income Housing Coalition What caused the home foreclosure crisis that came to a head in the fall of 2008 and precipitated the “Great Recession” is hotly debated. Explanations fall along predictably partisan lines. One side cites too much government interference in the marketplace, while the other side sees an unfettered marketplace allowed to run amok.

The undisputed result was that too many people took out home mortgages that they could not afford and too many lenders made loans that they knew the borrowers could not afford. It did not matter to lenders, because they could sell off the loans to the secondary market, take the cash, and move on to the next borrower who confused home buying with a get-rich-quick scheme.

In the name of “wealth-building,” the home buying push that led to the Great Recession will be remembered as a massive transfer of wealth out of low and moderate income African-American and Hispanic communities into the hands of major financial institutions and their investors. Not only has no one in a position of responsibility at these institutions been punished for the devastation of individual lives and whole neighborhoods, but the federal taxpayers bailed out most of these institutions, while providing too little, too late to the people who lost their homes and their assets.

Today, there is much consternation about the “softness” of the home-buying market and constraints on access to credit for potential home-buyers. We should ask ourselves why a low income renter whose neighborhood was blighted, who has not had a raise in years, who has friends and relatives who are still out of work or are underemployed, would believe that buying a house is a good thing to do. Low income people have every reason not to trust anyone who tells them buying a house is good investment. What happened to their homes is fueling mistrust that will stay with foreclosed families for at least a generation.

The conflation of “house” with “asset” in the policy and political narrative of the 1990s and 2000s led us lose sight of the meaning of “home.” Home came be idealized as a single family residential structure that the occupants “owned” by virtue of having borrowed money from a bank that is to paid off with interest in 30 years. Home as sanctuary and the center for family life became a secondary meaning and renting was relegated to a second class form of tenure. The federal government subsidizes home-owners through its support of the mortgage market, through the tax code, and through direct expenditures by HUD and USDA in amounts that dwarf support for renters.

Meanwhile, through the housing boom and bust and tepid recovery, the rental housing crisis only has gotten worse. The Joint Center on Housing Studies at Harvard University issues its “State of the Nation’s Housing” report each year. The 2000 report cited 5.4 million very low income1 renter households who received no housing assistance paying over half of their income for housing and/or living in substandard housing.2 The 2014 report shows that two-thirds of renter households with incomes less than $15,000 a year spend more than half of their income for housing, as do 34% of renters with household income between $15,000 and $29,999.3

Analysis of 2012 American Housing Survey data by the National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC) shows there are 10.16 million extremely low income

The rental housing shortage has been exacerbated by the foreclosure crisis, as former homeowners moved into the rental market and potential homebuyers stayed in the rental market. An already inadequate affordable rental housing market has had to absorb the growing renter demand. In 2013, rental vacancy rates declined again to their lowest level since 2000 and rent increases continued to rise well above inflation.7

A major contributor to the rental housing crisis for very low and extremely low income households is the reduction of federal government support with cuts to HUD and USDA programs. A fiercely divided Congress and a worrisome federal deficit have resulted in severe cuts to all direct spending on low income housing. Both parties refuse to raise revenue to reduce the deficit, much less invest in affordable housing, schools, transportation, infrastructure, or a host of other neglected core social needs.

In the name of “wealth-building,” the home buying push that led to the Great Recession will be remembered as a massive transfer of wealth out of low and moderate income African-American and Hispanic communities into the hands of major financial institutions and their investors.

Why is rental housing a good investment? First, over one third of all American households are renters and virtually everyone is a renter at some point in his or her life. Second, renting makes the most sense for people who expect to live somewhere for less than a few years, because the transaction costs of buying and selling will likely exceed any equity they might accrue. Renting also makes more sense than buying for people whose employment has any uncertainty to it, like variable hours or the potential of lay-offs. Responding to reduced economic circumstances is much easier with a lease than a mortgage. Third, people at different stages of the life cycle may be better off renting than owning, especially if they are not in a position to maintain a house. People whose jobs require a lot of travel or older people may be happy without the bother of yard work or roof repairs. Certainly many people prefer the freedom and flexibility that renting offers.

Most importantly, extremely low income and many very low income families would be better served by strong rental housing market that offer them choices of where to live than they are by an array of inadequate, under-resourced, and outdated programs or being prematurely thrust into the mortgage market.

The most fundamental goal of housing policy should be housing security, which is what the 1949 U.S. Housing Act prescribed: a decent home and a suitable living environment for every American family. Housing security means paying what you can afford to live in a home that is adequate for your needs and from which you move only by your own choice. Housing security means not living in fear of eviction or exploitation or violence or hazards to your health. Housing security means also being able to afford healthy food, appropriate medical care, transportation to get where you need to go, and other necessities, with enough left over to be able to save for emergencies, education, retirement, and maybe even a down payment on a house. Housing security as a renter is a necessary precursor to borrowing to buy a house.

Recovery from the foreclosure crisis will take a long time; people need to heal from the trauma and reestablish trust with the institutions that failed them. Public policy should focus on getting back to basics. Does every community have enough housing that all the people who live there can afford? Or enough housing so that no child in its schools is homeless or churning from one home to another and one school to another? Or enough housing to assure that its elders live out their years with dignity? Or enough housing that its citizens with disabilities can lead productive lives?

The problem is not a lack of resources. The federal government will subsidize home-ownership through the tax code to the tune of $241 billion in 2015. These tax “expenditures” are the mortgage interest deduction, the property tax deduction, the capital gains exclusion, and the net imputed rent exclusion.8 NLIHC has proposed modest changes to the mortgage interest deduction9 that would not only raise enough revenue to solve the rental housing shortage, but will give a tax break to many more low income homeowners than claim the mortgage interest deduction now. NLIHC’s proposal will not cost the federal government any more than it already spends on housing and it will make the tax code fairer and simpler.

The solution to the rental housing crisis is in plain view. Modest adjustments to the mortgage interest deduction will raise enough revenue to fund rental housing programs for ELI households. All it takes is bipartisan political will, which unfortunately is in short supply.

1 Very low income is 50% of the area median or less.

2 Joint Center for Housing Studies. (2000). The State of the Nation’s Housing. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

4 Extremely low income is 30% of area median or less.

5 The general accepted standard of housing affordability is no more than 30% of household income.

9 Learn more about NLIHC’s proposal at https://nlihc.org/unitedforhomes

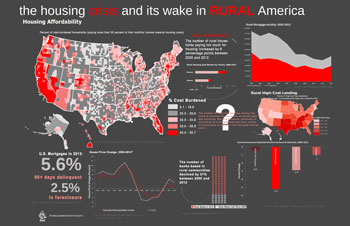

The housing crisis and its wake in rural America

The housing crisis and its wake in rural America