For more on this topic, read the July 2014 issue of

Gail Burks, President & CEO, The Nevada Fair Housing Center, Inc.

Gail Burks, President & CEO, The Nevada Fair Housing Center, Inc.

Do you believe that the housing crisis is over?

As I contemplated this question, my mind wandered to a quote given to Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart by his law clerk in an effort to define obscenity – “you’ll know it when you see it”. In rural America, no other quote could so aptly describe the housing scene. From an evidence based perspective, three continuing themes support the premise that we have not seen a recovery. First, to date, proposed solutions have not been tied to real time field data from rural areas of the country. Rent a vehicle and drive in any direction and you will know rural America when you see it, along with the attendant housing problems…

For more on this topic, read the July 2014 issue of .

In 2008 the U.S. economy fell off a cliff. Depending on your perspective it either slipped or was pushed from that precipice by the housing markets. But after six years where are we? How were rural Americans impacted, and are there lingering effects from the crisis? Rural Voices assembled four of the most knowledgeable experts in the affordable housing world to help answer these complex questions and provide insights on how to improve rural housing conditions in the wake of the housing crisis.

Gail Burks, President & CEO, The Nevada Fair Housing Center, Inc.

Gail Burks, President & CEO, The Nevada Fair Housing Center, Inc.

Do you believe that the housing crisis is over?

As I contemplated this question, my mind wandered to a quote given to Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart by his law clerk in an effort to define obscenity – “you’ll know it when you see it”. In rural America, no other quote could so aptly describe the housing scene. From an evidence based perspective, three continuing themes support the premise that we have not seen a recovery. First, to date, proposed solutions have not been tied to real time field data from rural areas of the country. Rent a vehicle and drive in any direction and you will know rural America when you see it, along with the attendant housing problems. Second, the design of programs such as the Neighborhood Stabilization Program (NSP) did not contemplate rural development issues such as the additional due diligence required on wells, open range, etc. Third, the foreclosure numbers are a consistent moving target. Depending on the state, defaults are not necessarily finalized within a set timeframe. The rule of law within the local community may extend, sometimes for years, the actual trustees’ sale. When obtaining data on foreclosure, it’s important to define the parameters. Until we can clearly identify the problem based on reality, solutions will continue to be illusive at best.

What factors defined the “housing crisis?”

Depending on which day and commentator you listen to it is the fault of the homeowner, bank or society in general. They all got it wrong. Nothing in society rises or falls based on one thing. In our sworn testimony for the Congressional body known as the Federal Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, we highlighted how various factors converged simultaneously to create the current market in our state or on a broader scale.

It is also important to note that the housing crisis must be viewed within the context of the greater economy in both the U.S and abroad.

Nevada consumers initially complained about predatory lending practices in 1999. By 2001, the Nevada Fair Housing Center, Inc. began to see an average of over four hundred clients per month with predatory lending issues. Clients presented cases that included such loan practices as appraisal fraud, flipping, high interest rate loan products, excessive prepayment penalties and violations of Federal law in the servicing of these loans.

No one can debate the need for legitimate non-prime (subprime) lending products. The subprime market served individuals with little or no credit, along with those recovering from a financial setback.

Until we can clearly identify the problem based on reality, solutions will continue to be illusive at best.

Traditional equity enhancements allowed a non-prime borrower to obtain credit. These often included verification of non-traditional credit (i.e. rental payments, utility bills, etc.), proof of one month’s reserve, establishment of an impound account and private mortgage insurance (PMI.) While the non-prime borrower might pay more for the cost of credit, that cost was directly related to lender risk.

However from approximately 2004 – 2007, the purpose and role of non-prime became lost in the zest to create profit driven securitized products. Non-prime mortgages mutated into fantasy financing. Out of this mutation grew a new breed of mortgage product, fueled by:

- No underwriting

- Lender failure to determine the ability to repay the loan

- Failure to fully amortize the payment

- Failure to establish impounds for insurance and property taxes

Many consumers received loan products that were not suitable based on their credit and income. When payments on “option” adjustable rate mortgages (ARMs) and pick-a-payment mortgages began to adjust, many consumers experienced payment shock.

No document loans also fueled the crisis. Traditionally, this standard product was only offered to self employed individuals with twenty percent down. However, brokers began offering the product to consumers on fixed incomes such as seniors and working families.

This crisis was further fueled by the joining of strange bed fellows. Providers of services- brokers, correspondent lenders, title companies, appraisers, real estate agents- formed alliances to make money. Sadly, some consumers sought to grab the brass ring and become ‘investors’ and share in the new get rich craze.

How, was the housing crisis different for rural areas than the nation as a whole?

Rural America experienced a crisis. In part, the financial meltdown contributed to a decrease in the ability to develop and leverage housing. Not only did consumers in rural America experience foreclosures but the development side was also impacted.

Mississippi County Home – Jimmy Smith – Creative Commons

Mississippi County Home – Jimmy Smith – Creative Commons

What are the long term ramifications for affordable housing?

No. As previously stated, the design of programs such as NSP did not contemplate the additional due diligence required for rural properties. In addition, foreclosure numbers are a consistent moving target. Until we can clearly identify the problem based on reality, solutions will continue to be illusive at best.

The guidelines for HARP failed to take into account the local real estate markets (all real estate is local) and the refinance rules that were in place with Fannie and Freddie due to receivership. In other words, if some markets were so upside down from an equity standpoint, refinancing was obviously not an option. Public trust is very important. Press announcements about programs that were not practical for the market caused many consumers to lose hope.

The goal of the HAMP program was admirable. However, execution was inconsistent. Consumers received various degrees of assistance. The common denominator with all the programs, lender participation, was voluntary. The consistent loss of paperwork by lenders, inability to reach lender staff, lack of coordination between lender departments, made the program difficult. Lenders do not do “one offs”; therefore, their goal was to incorporate the program into the lender’s automated systems. This took years. Moreover, from a legal standpoint, many lenders could not make the final decision absent investor sign off. Marketing indicated that all lenders utilized the same process. In reality, this was not the case. Later in the program, an effort at centralization to send consumers through one computer system hurt past efforts. Due to various lender pools, investors, and legal pooling service agreements for mortgage backed securities, the marketing of assistance did not match the reality. Despite the good field work again, consumers lost faith in the system.

As consumers lost faith in various announced programs, the rise in strategic defaults increased. The attitude of “why pay for something that is worth less” seemed to overshadow the idea of contract obligations.

In Nevada, the passage of legislation to create a mediation program actually encouraged lenders to work with consumers more than all the federal programs. Similarly, litigation in some areas provided relief.

What are the long term ramifications for affordable housing?

Sometimes old methods work best. As a product of rural America, many programs have disadvantaged communities in providing a false sense of security. The long term ramifications are a stunted growth in outlying areas

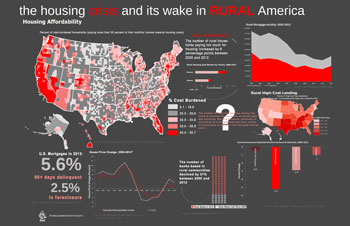

The housing crisis and its wake in rural America

The housing crisis and its wake in rural America