THE RURAL HOUSING ECOSYSTEM IS UNCERTAIN

Jobs and employment conditions have traditionally been a bellwether and leading indicator for housing trends. While the unemployment caused by COVID-19 is unprecedented and unpredictable, such high jobless rates signal the potential for serious concerns across the housing spectrum. Many Americans have been buoyed by large scale federal unemployment benefits and economic stimulus. But some of those resources are ending and the CDC’s eviction moratorium is slated to end March 31, 2021. If rural unemployment rates remain high the collateral impacts to almost all sectors of the housing market could be substantial – notably the ability of unemployed households to make rent and mortgage payments.

Housing instability is particularly concerning for rural renters who typically have lower incomes, less savings, higher unemployment due to COVID, fewer protections and less ability to weather economic shocks. According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s most recent PULSE survey, approximately 18 percent of renters nationally are behind on their rent payments and 13 percent have no confidence in their ability to make next month’s rent.

There are also concerns on the supply side of rural housing markets. Many landlords have declining rental income because of policies and adjustments related to the pandemic. Rural housing market dynamics are also distinct in this realm. On one hand, the levels of “free and clear” homeownership without a mortgage are highest in rural America and this could help provide stability for many homeowners during the economic crisis. But in rural rental markets, rental properties tend to be smaller and are also more likely to be owned by individuals who may be less able to weather a loss of rental income. Approximately 45 percent of rural renters live in single-family homes, compared to only 19 percent in cities and 34 percent in suburbs.

RURAL RESILIANCE AND PERSEVERANCE

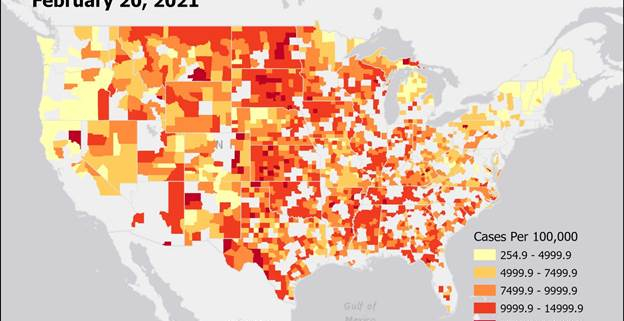

The last year has been difficult for every community in the United States – and the entire world. Daily life has been disrupted, millions have lost their jobs, and every day, 215 rural Americans lost their lives[1] to the virus. COVID-19 is an unprecedented event and comparisons are invariably flawed. There is general consensus that the 2008 economic crisis came later to rural America and the initial shock was not as great as in some urban and suburban markets. But the economic, social, and political fallout from that crisis lingered and the recovery was much slower for many rural communities. There are signs of positive trends in infection rates, treatments, and vaccinations – but the economic and social picture is still unclear. Rural Americans have always shown remarkable resilience and perseverance. These attributes – as well as rural recognition, strategies and policy solutions will be needed in our recovery from a difficult 365 days – and counting.

[1] Daily average total.